One step back, two steps forward.

Fun with Go, Chi, Routers, and Google Cloud Functions

Sometimes, the best way to progress is to take a step back, gather some perspective, and push forward. When trying to learn a new technology, I typically follow a tutorial or a guide I find online. I’ve found it is my best bet to get started with something new.

But sometimes it’s not.

Especially if it lacks a structure that you’re going for. That’s what I ran into this week. I was surprised. So, I took a step back and used my own approach. I’m really happy with what I came up with, so I thought I’d share.

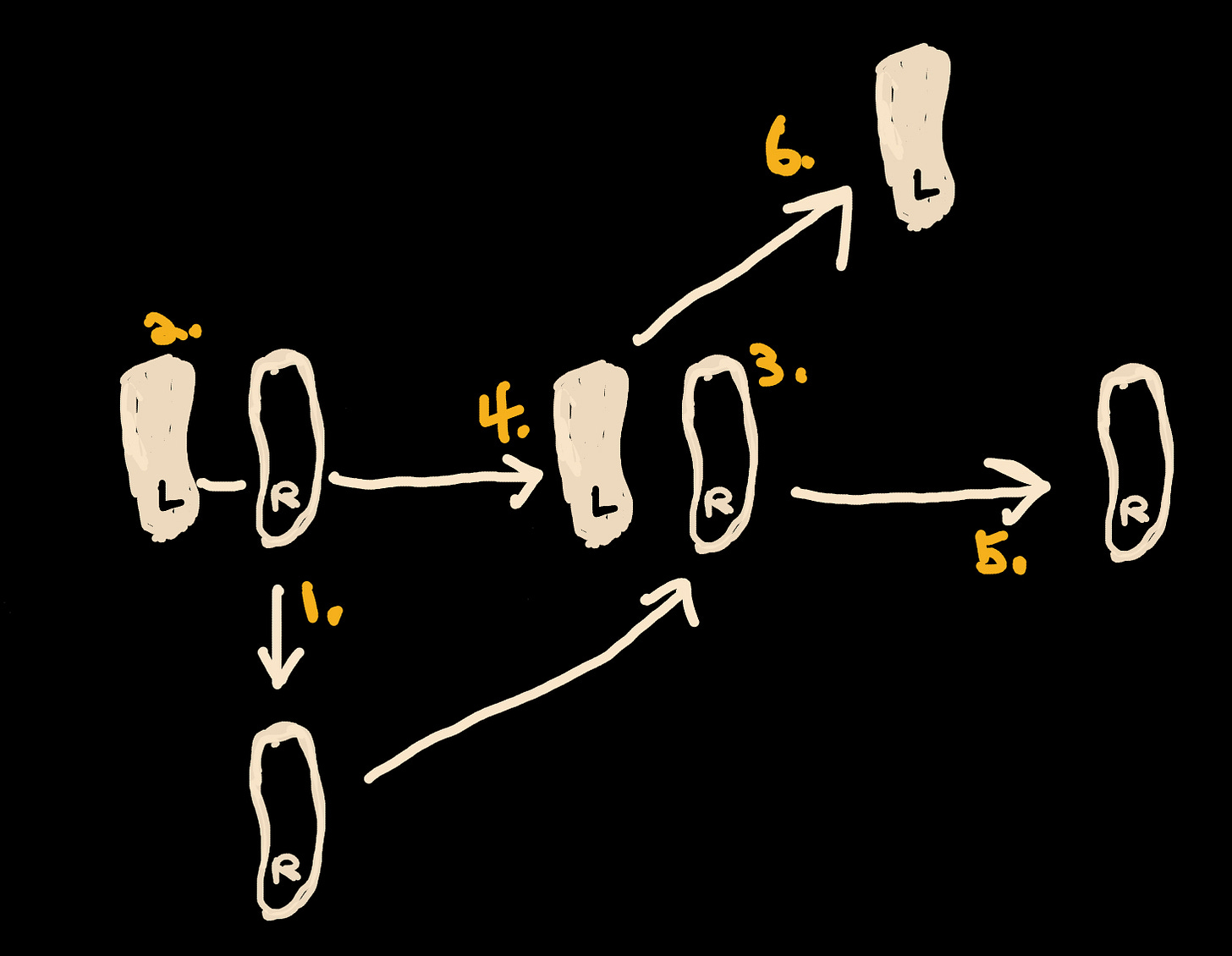

I was recently tasked with building a lightweight API demo using Google Cloud Functions. These are what are known as Serverless or Function as a Service. I’m well versed in doing this on AWS with API Gateway and AWS Lambda, so I looked forward to taking a spin with Google Cloud’s tooling.

If you follow the tutorial, Create and deploy an HTTP Cloud Function with Go, it drops you into a project that looks something like this:

func init() {

functions.HTTP("Handler", Handler)

}

func Handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintln(w, "hello, world")

}If this looks alien to you, don’t worry; there are two key takeaways here:

You need to initialize your code in the init() function to inject your code into their functions library.

You need to pass in a HandleFunc. If you’ve written any web server work in Go, you might recognize that function signature for HandleFunc. This is from the Go standard library in net/http.

Great. This works fine for a really basic example. But what if I want to use routing with a URL path (foo.com/api/foo) or handle HTTP requests like GET or POST in a specific way? This is a common pattern in RESTful API services: You wire up an HTTP multiplexer (router) to your request processing pipeline. So, I performed web searches and found a few results (1, 2). Oddly, both did something like this:

var mux = newMux()

func Handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

mux.ServeHTTP(w, r)

}

func newMux() *http.ServeMux {

mux := http.NewServeMux()

mux.HandleFunc("/one", one)

mux.HandleFunc("/two", two)

return mux

}

func one(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("hello from one"))

}

func two(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("hello from two"))

}In the example above, a mux (router) is set as a global variable and then consumed by the handler. It works, but I don’t love passing in variables this way if I can avoid it. Despite the code smell on setting that global variable, there is a valuable lesson in the code. The clever part is here:

func Handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

mux.ServeHTTP(w, r)

}The HandleFunc calls the Handler interface ServeHTTP method, allowing all router information to pass through. I knew there had to be a better way to do this than to declare a global variable, and I also wanted to use my favorite router in Go: chi. So, after a little bit of hacking around, I came up with this pattern:

func init() {

router := newRouter()

functions.HTTP("Handler", newHandlerWithRouter(router))

}

func newRouter() *chi.Mux {

r := chi.NewRouter()

r.Route("/api", func(r chi.Router) {

r.Post("/foo", fooHandler)

r.Post("/bar", barHandler)

})

return r

}

func newHandlerWithRouter(handler http.Handler) func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

return func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

handler.ServeHTTP(w, r)

}

}This was a clean and simple solution to my problem. This allowed me to avoid setting a global variable for the router while still letting me inject my router logic into my handler. Now, I can develop my Cloud Function like any Go server, giving me complete control of adding all the advanced tooling I want.

While I am surprised I couldn’t find this example online, I’m glad I took a step back from what I was reading, recognized the patterns I had in front of me, and experimented with integrating a solution I was familiar with. Now, I have a solid foundation for developing the rest of my project in a highly composable way.

Notable Links of the Week

Recursive racks

I love everything about the ideas behind “recursive racks,” as always; Henry’s explanations of the mechanisms and possible uses are fascinating.

A Mysterious Design That Appears Across Millennia | Terry Moore | TED

I’m obsessed with Penrose Tiling, so I had to check out this video. I loved the content and wished it wasn’t only a six-minute video. I consider this a jumping-off point in future research.